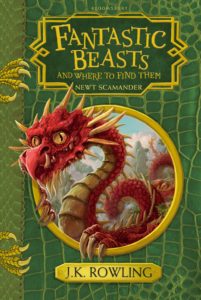

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them by Newt Scamander | Book Review

Disclosure: I did not receive any compensation for this review. But if Newt Scamander wants to be best friends, the offer will be accepted. Illustrations are copyright of Jim Kay and Bloomsbury. Images are used for reference and commentary.

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them was commissioned in 1918 and first published in 1927. I do not know how Scamander convinced the proprietor of Obscurus Books that it took him nine years to write a compendium that blatantly excluded beasts such as the Thunderbird, which is known to anyone familiar with the American wizarding school Ilvermourney. I splinched my manuscript? I was obliviated? Thunderbirds are no-go? Whatever his reasoning, Augustus Worme seems to have been satisfied. The book has never been out of print and we now have an updated edition 90 years later.

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them was commissioned in 1918 and first published in 1927. I do not know how Scamander convinced the proprietor of Obscurus Books that it took him nine years to write a compendium that blatantly excluded beasts such as the Thunderbird, which is known to anyone familiar with the American wizarding school Ilvermourney. I splinched my manuscript? I was obliviated? Thunderbirds are no-go? Whatever his reasoning, Augustus Worme seems to have been satisfied. The book has never been out of print and we now have an updated edition 90 years later.

The foreword for this new edition, written by Scamander himself, touches on several subjects. First, his involvement with Muggle charities. When Fantastic Beasts was first made available to Muggles in 2001, the proceeds went to Comic Relief. The foreword for that edition was provided by Albus Dumbledore, which is odd but not impossible, as its publication and distribution may have been several years in the making. However, Scamander’s statement that they “were both delighted that the book raised so much money for some of the world’s most vulnerable people” will surely serve to fuel several Dumbledore conspiracists.

On the subject of such persons, Scamander bites back at Rita Skeeter’s scathing biography of him. If you read Skeeter, we are not friends. If I could, I would chew up that beetle and anoint my quills with her poison. Scamander rebuts her accusations, which align him with the phony peacocks of this world such as Gilderoy Lockhart. He also recounts – to an extent – his run-ins with MACUSA (the Magical Congress of the United States of America) and dark wizard Gellert Grindelwald.

Note: Please stop sporting the Deathly Hallows symbol on clothing, jewelry, skin etc. It is grossly disrespectful to Gellert Grindelwald’s victims and their families.

Note: Please stop sporting the Deathly Hallows symbol on clothing, jewelry, skin etc. It is grossly disrespectful to Gellert Grindelwald’s victims and their families.

The foreword is followed by an introduction, outlining the definition of “beast” and giving a brief history of their relations with both Muggles and the magical community. This is tempting to skim, especially if you have bad eyesight like me, but the information is necessary for the novice. If you find your attention wavering I recommend listening to the audio book, read by the author. More on that marvelous experience later.

Because this book is meant to be sold to the Muggles as a work of fiction, there are no photographs. This displeases me and I hope to one day get my fingers on a proper copy. Preferably signed by the author. And personalised. To supplement the lack of photographic evidence, detailed illustrations have been provided by renowned Muggle artist Jim Kay. His depictions of various beasts are striking, but he seems to have something of a Doxy fetish, as they appear frequently throughout.

Because this book is meant to be sold to the Muggles as a work of fiction, there are no photographs. This displeases me and I hope to one day get my fingers on a proper copy. Preferably signed by the author. And personalised. To supplement the lack of photographic evidence, detailed illustrations have been provided by renowned Muggle artist Jim Kay. His depictions of various beasts are striking, but he seems to have something of a Doxy fetish, as they appear frequently throughout.

There are many magnificent (and a few mundane) creatures to be found within the book. My favourite is the Snidget, a small round golden bird, that originally took the place of the Golden Snitch, but is now an endangered species. Curse those Quidditch squishers! Other notable beasts are the Antipodean Opaleye – the native dragon to New Zealand – and the Knarl, a suspicious creature that greatly resembles my hedgehog kin. A few others that I recommend leafing through the pages for are the Demiguise, the Occamy, and the mischievous Niffler.

There has been some contention between myself and my human companion as to the validity of Scamander’s assertion that “the Niffler is a British beast.” I maintain that Scamander is the genius Magizoologist and his expertise should not be questioned. She insists, due to its hybrid appearance of a monotreme-marsupial, that it is “Straight-up Aussie, bro.”

There has been some contention between myself and my human companion as to the validity of Scamander’s assertion that “the Niffler is a British beast.” I maintain that Scamander is the genius Magizoologist and his expertise should not be questioned. She insists, due to its hybrid appearance of a monotreme-marsupial, that it is “Straight-up Aussie, bro.”

There are a handful of new beasts, such as the Hidebehind, the Snallygaster, and the Wampus Cat – which I am convinced to be a relative of the Great Rumpus Cat. The other namesakes of the Ilvermourney houses are included, with the exception of the Pukwudgie. I suspect this is due to it having the classification of a “being” rather than a “beast.” Curiously, the Swooping Evil is not featured. Neither is the Rougarou.

In accompaniment to reading the book, I also listened to it on audio, read by the author. Hearing him read his own words was a remarkable experience, heightened by the added soundbites of each of the fantastic beasts in their habitats. I felt as if I was right there with Scamander, taking in the wonder of these magnificent creatures first-hand.

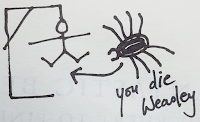

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them has been my favourite book for many years and I am even more enamoured with this updated edition. My last copy was second-hand and had been scribbled in.

Note: Unless your name is Newt Scamander, do not scribble in this book!

Note: Unless your name is Newt Scamander, do not scribble in this book!

I only wish this edition had been in publication while I was living in America. To think I resided in Manhattan without knowledge of MACUSA or these classified beasts!

Note: Yes, my hedgepiggy presence in New York City was illegal. I like to think this makes me a fantastic beast.

In conclusion, I highly recommend this updated edition of ‘Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them.’ If possible, purchase a copy for yourself, or acquire one from a friend or your local library. I also encourage you to visit the websites for the charities Lumos and Comic Relief.

In addition, if anyone can let me know how to get in touch with Mr Newt Scamander, I would be beyond ecstatic. It is my greatest dream to meet him and I promise that if I ever do so I will not eat any of his Bowtruckles. Maybe one.